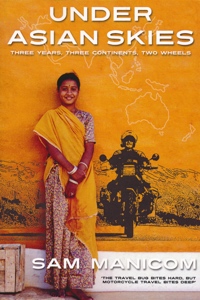

Under Asian Skies – Excerpts

How To Order

In the UK? Click here to order a signed copy direct from Sam.

…At around 5pm this world turned flaming orange. Everywhere was one shade of riotous orange or another, and the eerie light was only broken by the odd silhouette of a palm tree or an ox cart moving slowly across the land. This light is particular to India and it almost wraps itself around you, making you too an integral part of the scene. This light is formed by the end of day sunrays working their way through hundreds of kilometres of air filled with smoke and dust particles. So gentle is the change into night that this slow moving world feels like it’s almost suspended in the glow, as if it will stay forever…

… There didn’t seem to be any system. The traffic appeared to have no rules other than ‘go forward somehow’. Battered Ambassadors heaved their heavy rounded bodies forward, lumbering around potholes. Three-wheeler rickshaws buzzed like demented flies, darting and ducking past the other road users. Big, beaten up buses belched clouds of smoke over everyone, and bullied their way along with a rather solid superiority. Their windows were decorated with shiny pictures of the gods Ganesh and Shiva or fat, non-smiling Buddhas. They had glittery tassels hanging and swinging like some sort of freak belly dance as the bus thumped through yet another hole. Garlands of bright orange marigolds framed the windows, and bold signs stated warnings and religious confidence. ‘Sound Horn Please’ and ‘God Is With Me’.

Big Tata trucks, subservient only to the almost kamikaze behaviour of the buses, arrogantly elbowed their way through the mess. Only fools, buses and cows got in their way. People-power rickshaws scuttled their sweaty way through the chaos, battling for tiny spaces. The rickshaw men looking wide-eyed at the constant mash of ever-changing threats, all of which had the power to crush them and their passengers out of existence as one would do with an irritating bug.

Big Tata trucks, subservient only to the almost kamikaze behaviour of the buses, arrogantly elbowed their way through the mess. Only fools, buses and cows got in their way. People-power rickshaws scuttled their sweaty way through the chaos, battling for tiny spaces. The rickshaw men looking wide-eyed at the constant mash of ever-changing threats, all of which had the power to crush them and their passengers out of existence as one would do with an irritating bug.

Cyclists were next down the food chain, with pedestrians being the lowest form of life. The latter though, still had to cross the street and did so with a combination of fatalism and pro-rugby agility as they handed off cars in their dash from one side to the other. The amazing thing was that it all seemed to work, until a cow got in the way that is. Cows are holy and know that they can get away with anything, so they did. They would aimlessly wander out into the snarling mess of the traffic, and the ‘flow’ really did somehow miraculously part for them. Perhaps in a past life Babu had been a cow, or perhaps, living on the taxi driver’s edge of life he was already dreaming of the form he would like to take in the next one…

… It was only a kilometre from our hostel into the centre of the town, but we still ended up being hassled by rickshaw wallahs, who seemed to think that it was most unseemly for visitors to be walking anywhere – they hassled mercilessly. By the roadside, the town dentist had laid out a strip of faded blue tarpaulin. He had carefully lined up his tools on this, most of which looked more like weapons of torture than dentistry equipment. Next to his tarp was an old kitchen chair, and it was upon this that his victims sat. He worked with no anaesthetic, and because of his impressive range of angled and long necked pliers, I suspected that he pulled more teeth than he fixed. His hand painted sign showed a large white set of gnashers set into unbelievably red gums; somehow the artist had got them to smile. To me that smile looked more like a grimace of pain.

Next to him was the town barber. A line of men stood waiting their turn to be trimmed with shiny scissors and a set of hand-operated clippers. They were shaved with an old-fashioned cut-throat razor, using richly foamed soap that the barber’s assistant kept ready-frothed. The white-chinned client in the chair looked at me over his shoulder in a fly-blown, silver-rimmed mirror that was hung on the crumbling graffiti-covered wall. ‘Sanjay loves Lina’ and ‘Bappa 4 Farida’. Next to the love grafitti were hand-painted signs advertising the local hospital – useful perhaps, if the shaving didn’t go too well. The painter of the sign had not been able to spell as well as he’d been able to paint, and for me, that did not inspire much confidence…

… He left me sitting knackered on my bike, like a mini island amidst flowing chaos, while he rode round the beat-up desperate-looking border town of Rauxul Bazar. The buildings were ramshackle and though most had been painted at some time, all were stained by dripping rusty water, mud splashes and years of collected grime. Dodgy characters slouched around in doorways, looking like faded, timeworn opportunists that were down on their quota of opportunities.

Garish advertising posters hung, either in tatters from the walls, or flapped gently in the listless breeze. Mangy scabby dogs slunk scavenging hopefully for a meal, from one rubbish pile to the next. Penny-sized black flies buzzed like miniature bomber planes from piles of shit in the street, to land on chunks of meat that hung under the faded awnings of the food stalls. Biting midges clustered around the moisture of children’s snotty running noses and rusting, wrecked, cannibalised trucks and cars lay by the roadsides. Even the holy cows looked as if they had been mentally afflicted by the dodgy air of this border town…

… Jaipur town is a centre of trade for the surrounding area, and as such it was incredibly busy. The traders seemed to either sell things that they had produced out on the farms, or things that those out on the farms would need. The colours were stunning: rich greens from the vegetables contrasted with bright oranges, reds, yellows and turquoises of women’s saris, and the pink and orange walls of the city and palaces provided the perfect backdrop. All this was going on under a bright blue sky and was spiced up by selections of vivid-coloured curry powders, the sparkles from the many jewellers’ shops and the gleaming white shirts that the men all seemed to favour. The streets hustled and bustled with those out shopping in the markets, the Ambassador taxis, the bicycle rickshaws, the chai sellers, the roaming stalls of stainless steel pots and pans sellers, and camels that moved imperiously through the crowds.

I watched an obviously wealthy lady doing her shopping in the market. This woman had the power that wealth brings, and she knew it. There was no hesitancy in her waddling stride and her fingers stabbed out at whatever caught her eye. She held her shoulders back and kept her chin up as she talked down to the market traders. Open fingers raised, she waggled her chubby wrists in disdain or disagreement; the traders would have touched their forelocks if that had been the custom. One stallholder, dressed in a white, loosely-wrapped turban, a long, dirty white shirt and a dhoti, bobbed and bowed at her every word as he scuttled around his wares, always making a show of selecting the best of everything. She demanded and received discounts wherever she shopped. Each purchase was thrust into the arms of the increasingly bow-legged coolie who was trailing along behind her. The crowds parted just as easily for her as they had done for the camel. She and the camels had mastered that perfect expression of superiority…

… We lunched on dahl, chapattis and chai at a truck stop – the more we took breaks at truck stops, the more I liked them. There were times when the usual overlanding fare of peanuts and raisins held no attraction whatsoever – nor did our lukewarm, odd-tasting water. Then we saw one, a road side cafe. Across some tree branches that had been machete’d roughly to size, strips of old sacking were strung to keep the dry, grit-laden breeze off the turbaned truck drivers.

… We lunched on dahl, chapattis and chai at a truck stop – the more we took breaks at truck stops, the more I liked them. There were times when the usual overlanding fare of peanuts and raisins held no attraction whatsoever – nor did our lukewarm, odd-tasting water. Then we saw one, a road side cafe. Across some tree branches that had been machete’d roughly to size, strips of old sacking were strung to keep the dry, grit-laden breeze off the turbaned truck drivers.

They were sitting or lying in the flapping shade on charpoys, bed-like affairs with wooden frames upon which a rough netting of sisal string is woven. The ground beneath the charpoys seemed to be layered with generations of spit, betel nut juice, old nails, bits of wire and washers. The air was full of the scents of spilt diesel, curried lentils, fresh baking chapattis and wood smoke. The fire in front of the cafe was loaded with a vast urn of bubbling chai…

…Isaac took us down dark, chilly alleyways and into what looked like private homes. Most carpet sellers seemed, as with the firework man in Varanasi, to double their musty-smelling workspaces with their living space. Most of the merchants seemed to be Afghans rather than Pakistanis, and some of them looked decidedly affluent, though their surroundings were basic and simple. Most of the merchants were wearing traditional Pakol hats, made with really coarse wool. From a distance, these looked like they had been made from layers of pancakes, but close up I could see that under the pie-crust top was a sort of inverted tube that had been rolled up to make a sausage thickness rim. The hats looked warm, but must have been quite itchy to wear. The colours of choice seemed to be beige or grey, with a few more flamboyant characters choosing vivid blues.

I too bought a carpet – they were too tempting to resist. I rather liked the idea that I’d be riding with a hookah pipe and a carpet on the bike. It wasn’t a logical thing to do, but I’d had enough of being sensible at that moment…

… As I hung on white-knuckled to the handlebars, I kept repeating to myself, ‘I’m going to Iran, I’m going to Iran, I’m going to Iran.’ If positive thought power was going to keep me safe, then I was going to overdose on it! When we eventually stopped, it took me nearly three hours to get rid of the adrenaline that my body had conjured up.

In the morning, the last 20 kilometres to the town of Nak Kundi was loose gravel, and in the dust as the bike fish tailed along, I felt as if I was back in Africa. Except when there are corrugations, this sort of gravel is fun to ride and you can do so at quite a speed, so long as you have the confidence that the surface isn’t going to change suddenly. It didn’t, and in Nak Kundi I bought the last two litres of bottled petrol the stall had. We were almost at the border, and though my visa had officially expired that day, I felt sure that if I played dumb then I’d have no problem…

…The first checkpoint away from the border wouldn’t let us through. ‘It is too dangerous for you to be travelling at night in this area,’ the olive-green clad soldiers told us authoritatively. ‘You park there. You go in morning.’ No sooner had we settled down, bodged a repair on the skylight and had prepared dinner, when another group of soldiers marched across to bang impatiently on the bus door. ‘You no stay here! You go now!’ the one in charge shouted at us. His face was reddened and spittle was flying from his mouth as he shouted and stamped his foot like a petulant child overdosing on power. The soldiers with him all had their guns pointing at us and looked as if they were itching to try them out. The head soldier’s angry enthusiasm was infecting them and they appeared to be more like a mob than a unit of a nation’s army. Most of them looked like teenagers in uniforms they’d borrowed from their fathers, and I couldn’t see one who looked as if he was safe handling a gun…

…The women of Tabriz respected the Moslem religion in a most traditional way. I didn’t see one woman on the street who wasn’t dressed in the long, loose-fitting black robes, with a black headscarf and veil covering their heads and faces. In Esfahan, many of the women had worn brightly coloured headscarves and had kept their faces uncovered. I’d been told that in the capital city, Tehran, the women were able to be even more flamboyant. But here in Tabriz it looked as if the streets were populated by men, and black ghosts. The only way I could tell a woman’s likely age was by the type of shoes and stockings she was wearing. If the shoes had a heel of some sort, they more than likely had a young owner. If the stockings that went with those shoes were sheer, worn without socks, then there was a good chance that the woman was young. I found it hard not to stare as I tried to work out who I was looking at. Older women averted their gazes but younger women would more than often give me a quick straight-eyed stare in return for a few seconds…